The last two weeks, Dana has shouldered the “burden” of this blog, so I am making up for it with a long post on a pressing issue. Forgive me in advance for the length, but I think you’ll find the subject a fascinating one!

There’s been a lot of talk in the presses lately about the subject of impeachment. How could I, a presidential historian, resist writing on it?

To be clear: I am not going to comment on the Mueller Report, Donald Trump, the Justice Department, or Nancy Pelosi. If you want to know what’s going on in current events, may I suggest one of the national newspapers, which have for the most part done an excellent job of covering the ongoing debate. Here’s a short list of reliable sources with links:

Instead, I think it more interesting to reflect on the irony that just one year ago (March 2018) we passed the 150th anniversary of the first presidential impeachment in American History. What’s more, by retelling the story, we can observe the parallels of history.

History is always with us. Blink your eye, and 150 years go by, and we’re still talking about the same subjects, and asking the same questions.

The Story

Let me paint the scene.

It’s 1868. The Civil War has been over for three years. The Republican Party controls Congress, but not the Presidency. Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Democrat, has been thrust into that office by the death of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. He is a Southerner, but he is loyal to the Union. Beyond that, though, there’s not much daylight between him and the former Confederates. Johnson is a white supremacist, and he believes in states’ rights.

(Library of Congress)

Many Republicans in Congress expected Johnson to come down hard on the South not only for the war itself, but now for the death of Lincoln as well. Instead, Johnson surprised everyone by offering the South lenient terms of readmission to the Union. All that southerners had to do was take an oath of loyalty to the Union. High ranking members of the Confederate government could even apply personally to Johnson for a Presidential pardon.

While Johnson made it easy for southerners to come back into the Union, he completely ignored the former slaves. They were now at the mercy of their former masters, who began enacting harsh laws (called Black Codes) to force them back onto plantations.

Johnson did nothing to stop the Black Codes, so the Republicans in Congress passed a Civil Rights bill declaring all persons born in the United States citizens, and entitling them to protection under the law. In other words, former slaves could now sue their employers for harsh working conditions and unfair business practices.

Johnson vetoed the bill, citing states’ rights. Republicans, in response, overrode his veto. And now we had a ballgame!

For Republicans, there was an additional problem.

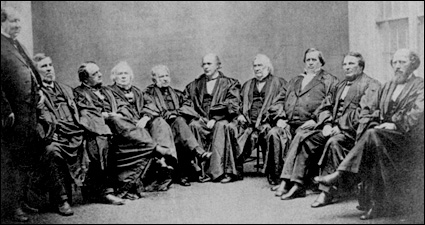

The Supreme Court wasn’t on their side! It had begun declaring laws passed during the Civil War unconstitutional, saying that many of them only applied during times of war. Republicans realized they would have a hard time keeping their Civil Rights Bill on the books, so in June 1866 they passed the 14th Amendment to the Constitution. Now natural-born citizenship, and protection under the law were constitutional guarantees–written in stone. The Court couldn’t touch it.

(Supreme Court Historical Society)

This brought on the second showdown between Congress and the President.

Johnson, of course, opposed the 14th Amendment. And–since an amendment requires 3/4 of the states’ approval for ratification–he counseled that the South refuse to ratify….which it did in unison.

Unlike a bill, though, the President’s approval is not necessary to amend the Constitution. Republicans therefore argued that Johnson was illegally involving himself in a Congressional matter, and many of them started calling for impeachment.

At the same time, they chose to punish the South for not ratifying the 14th Amendment. In March 1867, they passed the Reconstruction Acts (again over Johnson’s veto), which stripped the states of their sovereignty and placed them under martial law until they passed the 14th Amendment, and/or registered all black men to vote.

(Study.com)

There was one more “hitch.”

The Reconstruction Acts required the President (as commander-in-chief) to name military governors of the southern “districts”–that’s what they were calling the states now. Johnson was supposed to work with his Secretary of War to make that happen. But the Secretary of War was Edwin Stanton, who had been appointed by Lincoln. Stanton supported the Republicans over Johnson, so Johnson fired him and put General Ulysses S. Grant in that office (Grant was non-partisan, and hated politics..just the sort of person Johnson was looking for).

(Library of Congress)

(Library of Congress)

Thinking that Johnson might pull something like this, Republicans had passed another law over Johnson’s veto–the Tenure of Office Act. It said that because a President needed Senate approval to appoint a cabinet officer, a President also needed Senate approval to fire them!

Three strikes, and you’re out!

When Johnson fired Stanton he technically broke a federal law. Congress had him right where they wanted him, and began immediately drawing up articles of impeachment.

A Political Process, Not a Criminal Court

Congress was treading on uncharted ground. Impeachment had been used in the past, but only against a member of the Supreme Court–Justice Samuel Chase–and he wasn’t even removed from office. What was more, the whole scenario had occurred sixty years ago.

(National Portrait Gallery)

No living member of Congress had ever actually seen the process of impeachment in action, and never had it been used against a President of the United States!

What was more, there were many lawmakers who doubted that Johnson had really committed an impeachable offense. After all, the Tenure of Office Act was a new law that changed the power structure between President and Congress…something that normally would require a constitutional amendment, and that would probably be struck down by the Supreme Court.

All that the Republicans could rely on, then, was theory.

Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution states that a federal officeholder shall be impeached and removed from office for “Conviction of Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” But there’s a problem. No legal definition existed for “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

The theory, then, is complicated. Because Congress makes the laws, it is up to Congress to define these infractions. And since Congress is elected, and its makeup changes over time, so too the definitions of these infractions can change. Furthermore, looking back to the framers of the Constitution, it appeared that they understood “high crimes” as abuses committed by federal office holders. Because Congress was a political body, and because the Presidency was the highest federal office in the land, then, impeachment and removal from office could be for strictly political reasons!

It didn’t matter if the Tenure of Office Act was questionable. Congress could impeach Johnson just because they didn’t like him!

And so they did! When the articles of impeachment came up for a vote in the House of Representatives, they passed by a vote of 126 to 47, with 17 abstaining. Impeachment, however, is only the process of indicting a person. Removal was up to the Senate.

(Library of Congress)

But the Senate was less sure that Johnson should be removed!

Without a Vice President, if Johnson were removed, the Senate Pro Tempore would ascend to the highest office. And that person was Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade–a radical Republican whom many senators liked even less than they did Johnson! Furthermore, conservative Republicans raised issue, particularly, with Wade’s support for divorcing America’s paper money from the gold standard. Was it not better, they asked, to keep Johnson in office temporarily and simply deny him another term? After all, 1868 was an election year, and neither the Democrats nor the Republicans were going to nominate him.

(National Portrait Gallery)

In the end, the Senate voted for Johnson’s removal by a vote of 35–19. However, Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution requires a 2/3 majority vote to remove an office holder. The Senate fell short of that number by exactly 1 vote!

In his 1956 Pulitzer Prize winning book Profiles in Courage, Senator John F. Kennedy immortalized Kansas Republican Senator Edmund G. Ross, whose decisive vote kept Johnson in office. Ross felt that removal would embarrass the country at a time when it needed to heal, and Kennedy interpreted it as an act of bravery, putting country above party.

(Library of Congress)

By the fall of 1868, the impeachment of Andrew Johnson had faded into history. That November, General Ulysses S. Grant was elected as the eighteenth President of the United States. Furthermore, the next year, the new President nominated Secretary of War Stanton to the Supreme Court, but Stanton died before he could take his seat. And as for Andrew Johnson, he was remembered fondly by southerners for his attempts to safeguard their liberties. In 1875, his home state of Tennessee returned him to the United States Senate. He arrived in Washington in time to participate in a special session of Congress, but he died later that year.

Legacy

Since the Johnson impeachment, only twice more has a President (Nixon in 1974, and Clinton in 1998) been threatened with impeachment and removal. In both instances, the process divided the country in ways that threatened the unity of the American people. The question was asked in both cases, is it wise to remove by force a president who was put in office by the democratic vote of the people? Is it not better to let the people be the final arbiter through the ballot box?

In the case of Nixon, the President settled the matter by resigning from office in August 1974. With Clinton, the people turned against the impeachers, and in the last two years of his term, the President’s approval ratings went up!

(C-Span.org)

It would appear then, that although impeachment is always an option when power is abused, it is not a very expedient one. The American people prefer to be the power that rewards or punishes elected officials. Put another way, a citizen of Wyoming does not want a Senator from Massachusetts making the decision for them.

For more information on the Johnson Impeachment, the Nixon Watergate Scandal, or the Clinton Impeachment, see the following sources:

- Peter Baker, The Breach: Inside the Impeachment and Trial of William Jefferson Clinton

- Michael Les Benedict, The Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson

- John F. Harris, The Survivor: Bill Clinton in the White House

- David O. Stewart, Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln’s Legacy

- Brenda Wineapple, The Impeachers: The Trial of Andrew Johnson and the Dream of a Just Nation

- Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, All the President’s Men

- Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, The Final Days

— m.a.n.